That organization she helped to found-Eliza’s “living legacy”-exists today as Graham Windham, thanks to Eliza and her fellow activists the oldest non-profit and non-sectarian child welfare agency in America. She was there in 1807 when the orphanage laid its first cornerstone, and she was indefatigable in her efforts to raise money and support the society, becoming its director in 1821. In 1806, along with several other social activists in New York City, Eliza was one of the founders of the first private orphanage in the city, the New York Orphan Asylum Society.

A single mother who by her 40s had delivered eight children, a foster mother to one little girl, and the wife of a man who had been orphaned himself in childhood, Eliza was passionate about the lives of children. 141st Street) from a public auction and remained the steward of the Hamilton family home.Īlthough Eliza’s story often ends there in the telling of the Hamilton history, Eliza didn’t just spend those next 50 years tending flowers in Harlem. But she was ultimately able to save The Grange (open to the public today as a New York State museum, 414 W. But Alexander’s rise to fame and glory was a wild ride that profoundly shaped the young American democracy, and Eliza was deeply proud of her husband.Īfter Alexander’s death the next year, Eliza was left impoverished, and her youngest child was only two-years old.

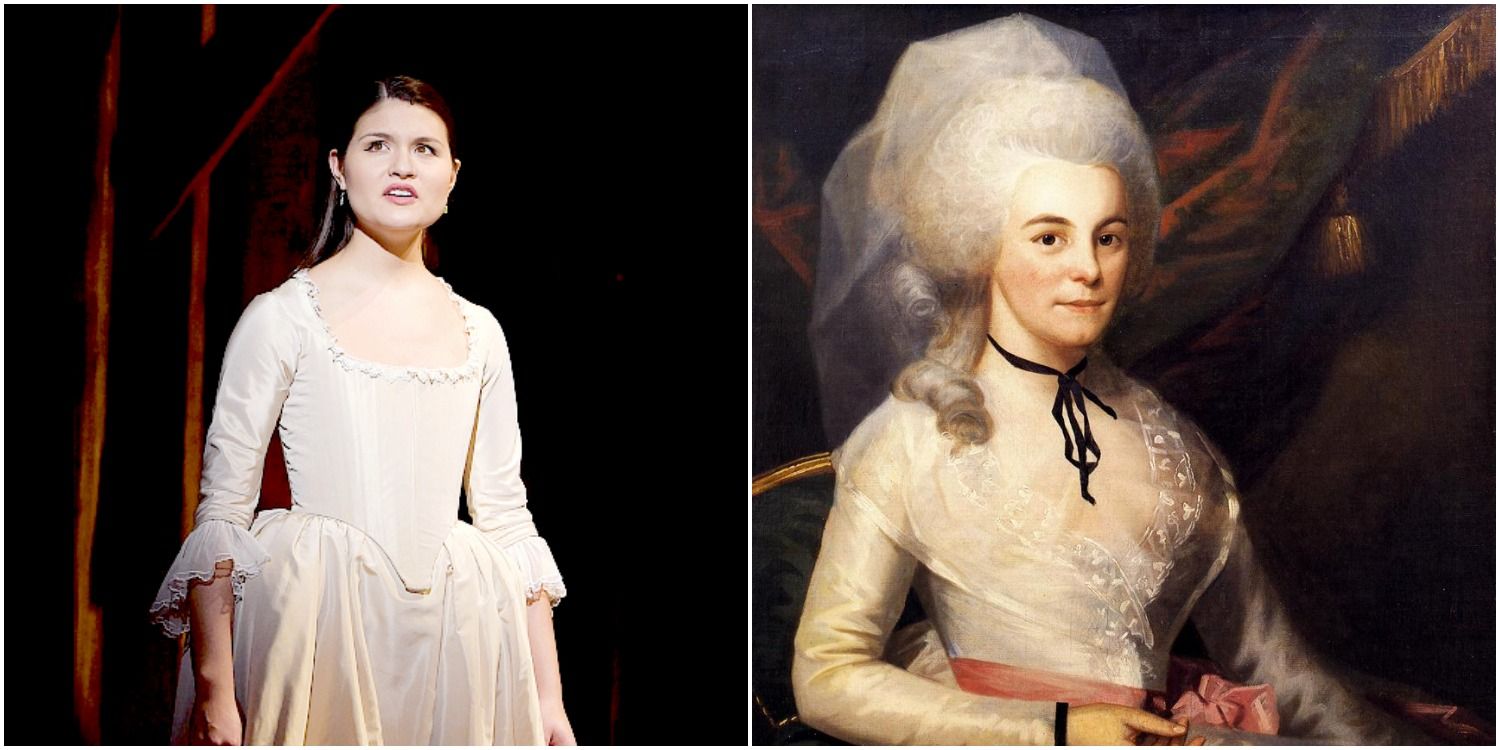

That marriage lasted from 1780 until Alexander Hamilton’s death in 1804, and, of course, there were some bumps along the way involving a unfortunate period of indiscretion with a certain Maria Reynolds. They also planned together an astonishingly ambitious garden that was years in the making. While they lived at times in upstate New York, in Philadelphia, and in army camps, their most important family home was a mansion in Harlem, known as The Grange, where they raised a passel children-some of them their own and at least one foster child, a little girl named Fanny, the orphan of a Revolutionary War hero. When they met again the next time, at an officer’s ball during the American Revolution, they were smitten and, soon, married. One of those young officers was Alexander Hamilton, who came riding in on horseback one day to deliver a message to her father. But instead of fancy needlework, they strung wampum for trade with the local American Indians, and, after a certain party in Boston, taking tea was not in fashion. The Schuyler girls fussed over finery and danced the minuet at balls with dashing young officers, first in British red coats and later in the “buff and blue” of the American troops, late into the night. During her girlhood in upstate New York, she and her sisters lived in a world that might be best described as a cross between every Jane Austen novel that you’ve ever read and James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans. Eliza carried on being fabulous for another 50 years after the death of “my Hamilton.” And not all the letters between Eliza and Alexander were burned, either.Įliza was born Elizabeth Schuyler in 1757, the daughter of an important landowner and Revolutionary War general. But if you’re an astute historian, you might notice that Alexander Hamilton was killed in that famous duel way back in 1804. Novemmarked the 167th anniversary of her death on that day in 1854 at the age of 97. The portrait is currently on display at the Smithsonian’s “Giving in America” exhibit.īy now everyone knows that Eliza Hamilton, the wife of Alexander Hamilton, burned her husband’s love letters before she died. Huntington, donated by Graham Windham in November of 2017. Alexander Hamilton (Elizabeth or Eliza) by Daniel P. Eliza’s Story The National Museum of American History is currently displaying this portrait of Mrs.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)